What has the digital done to our listening?

|a bro and his bud|

A tiny, white piece of plastic plugged a pinkish ear. I remember the sight well because of the thoughts and emotions it stirred in me. It wasn’t that I’d never seen an AirPod before. They’d dropped a year earlier, around Christmas, 2016 and quickly proliferated—comically punctuation-shaped inserts that seemed to put everyone’s head in air quotes. But I’d never seen one in my university classroom.

The pinkish ear was attached to a white teen, clad in sportswear and sitting in my class, The Smartphone and Society. He was looking directly at me with clear eyes and a neutral expression. Bewildered, I returned his gaze while my lips formed shapes about Bell Telephone Laboratory's Claude Shannon and his article "A Mathematical Theory of Communication."

What the fuck? Am I really seeing this? Did he just forget to take it out? Wait, that thing can’t be ON, can it? What is he listening to? Am I that boring? Does this happen to other faculty? Whoa, is he maybe trolling me? His face looks so earnest, though. What is he thinking?

I tend to walk around the room while I talk, as though I might, through bodily proximity, infect my students with my own enthusiasm for media studies. This allowed me to cruise by bro's desk and mutter “Remove that” under my breath, never breaking stride in my explication of Shannon’s revolutionary theory—the one that made all our digital devices possible.

|the sonic roots of the digital|

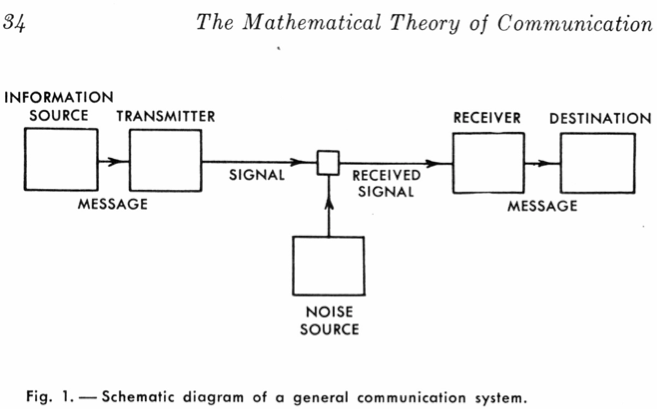

This mathematical theory of communication, I explained, was actually designed to eliminate audible noise. In 1948, the year Shannon had his epiphany, his employer’s parent company, AT&T, sold its 30 millionth telephone subscription. Turning a human voice into a varying electrical current and sending it across a telephone line was a noisy business. The world—even the phone line itself—was full of randomly jiggling electrons that degraded the desired signal. AT&T faced a crisis of success: as its customers and its miles of cable multiplied, noise and interference exponentially increased.

Shannon’s theory made the telephone voice quantifiable as the ones and zeros of "information," turning the noise problem into, more or less, a math problem. Shannon immediately recognized implications far beyond the landline. Not just voices, but pretty much anything could be transmitted as information. Paired with the transistor technology invented at Bell Labs that same year, information theory set off the digital revolution.

The tiny AirPod now being furtively fished out of a youthful earhole was just one more product of a theory designed to vanquish noise forever. And yet, as much as I had tried to play it cool, the mere sight of the AirPod in this context had created interference in my own communicative flow.

Looking back on it today, my split-second cycle of confusion, indignation, and insecurity at the sight of an AirPod in the classroom seems rather quaint. However, way back then—in the late teens of the twenty-first century—many of us still clung to a few tatters of a shredded social contract. These blurry remnants stipulated that we owed one another at least a cursory performance of listening when we found ourselves face to face.

I was gradually getting used to losing an increasing percentage of eyeball time to the computer screens on my students’ desks, but it hadn’t occurred to me that I might start losing ears too.

But lose ears I did: at first singly, and then in pairs. Sometimes, giant headphones would be situated atop the student head so as to only half-conceal the hearing organs of their owner—a perch of plausible deniability that perhaps, in total, lent me an ear?

While these communicative blockages remained the exception and not the norm, they happened frequently enough to make me wonder what the hell was going on. Were they all really multitasking? Could some actually be amplifying my voice? Or did they simply feel naked and unsafe without something in their ears? (We'll explore some of these possibilities in future editions.)

|a crisis of listening|

I’ve since learned (with some relief) that I’m not the only professor dealing with electronic ear gear in the classroom. In fact, listening is divided in seemingly every setting. According to The Wall Street Journal, even medical doctors are having to attempt earbudectomies on patients at the start of office visits. My wife, a clinical psychologist, sometimes has to cajole her patients into de-podding during their sessions.

You could say that this divided or selective listening is really a well-deserved rejection of elite authority—and you wouldn't be totally wrong. But think about that last example, from my wife's office. The symbolism could hardly be more on the nose: people in therapy are having trouble listening even to themselves.

And to state the obvious, this is not just a "kids today" phenomenon. Adults of all ages spend large chunks of their waking hours budded up. My wife tells me she no longer removes her Beats as a sign of respect at the grocery store checkout (and to be fair, since the pandemic, the worker at the register is often wearing earbuds too). I write and think and talk about this stuff all the time but it's a common occurrence in my household for everyone to be plugged in at once—calling everyone to dinner has become a hassle.

To really make sense of our digital ennui, we have to go back to the sonic roots of information technology.

For all the uproar about "screen time," I believe the noise-canceling headphone or earbud is actually the most potent symbol of our current digital plight. After all, noise-cancellation was the entire point of information theory. Digital technology was designed to free us from noise so we could listen to one another more clearly. And yet, you don't need me to tell you that life feels noisier than ever. Or that polls regularly report that a majority of Americans feel isolated and unheard.

I believe that our fixation on screens has obscured some central factors in the epidemic of digital loneliness and alienation. To truly understand what's going on, we need to return to the sonic roots of the digital. We need to explore the central paradox: How did a miraculous anti-noise, listening technology make it so hard for us to listen to one another, to ourselves, and to the world around us?

In my next installment, I'll explain an under-appreciated aspect of Shannon's theory—one that makes our current communicative impasse a lot more understandable. And in future newsletters, we'll explore ideas for a listening revival. The true solution to digital ennui is learning to listen again.