Horror Film Sound Designer Graham Reznick on Crafting the Uncanny

Graham Reznick is a multifaceted sound designer, screenwriter, director, and musician, best known for his work on indie horror films like Ti West's X and the critically acclaimed video game Until Dawn]. In this episode, Reznick discusses Rabbit Trap, a film based on Welsh folklore blending analog synthesis with supernatural soundscapes.

Host Mack Hagood and Reznick begin talking about horror sound design as a technical and creative process, examining how he crafted specific uncanny soundscapes in the film. The conversation then expands to the evolving relationship between sound design and musical scores in horror films, Reznick's limited series on Shudder called "Dead Wax: A Vinyl Hunter's Tale", and a discussion of haunted media, sensory deprivation, brainwave entrainment, self-improvement tapes from the 1970s, and other Halloween-appropriate topics!

Members of Phantom Power can hear our ad-free, extended version, which includes Reznick's world-record breaking work as a writer on the video game Until Dawn. Last but not least, we find ‘What’s Good?’ according to Graham, where he recommends things to read, do, and listen to!

Join us at phantompod.org or mackhagood.com! That’s also where you can also sign up for our free Phantom Power newsletter, which will drop on the second Friday of every month and feature news, reviews, and interviews not found on the podcast.

Chapters

00:00 Introduction to Phantom Power

01:19 Meet Graham Reznick: Sound Designer Extraordinaire

01:59 Rabbit Trap: A Sound-Centric Horror Film

02:29 Graham Reznick's Career Highlights

04:00 Phantom Power Membership and Newsletter

04:52 Interview with Graham Reznick Begins

05:00 Rabbit Trap: Plot and Sound Design Insights

10:40 Creating the Uncanny Soundscape

14:11 The Evolution of Sound Design in Horror

20:56 Sound Design Techniques and Tools

26:33 Exploring the Fairy Circle Scene

35:48 Dead Wax: A Vinyl Hunter's Tale

39:58 The Allure of Forbidden Media

43:31 The Evolution of Online Culture

44:34 Magic, Dark Arts, and Haunted Media

46:54 Sensory Deprivation and Inner Worlds

49:25 The Power of Sound and Music

52:45 The Impact of Individualized Media

Transcript

SVR: SpectreVision Radio.

Intro: This is Phantom power.

Rabbit Trap: Your shadow has been gifted many names: Golin Demon, Fairy. It is your forgotten child, but nature will not abandon her children. She gifts the music. You'd only dream. You can hear this music if you wish, but you must listen beyond fear. Beyond understanding beyond shame. Listen to the soil, go down into the dark and listen.

For the earth is a body, and the body is where your secrets live.

Mack: Welcome to another episode of Phantom Power, a podcast about sound. I'm Mac Hagood. My guest today is Graham Reznick, sound designer of a new film called Rabbit Trap, a film that is very much about sound. Electronic Natural and Supernatural. Rabbit Trap is a psychological horror film based on Welsh folklore, written and directed by Bryn Chainey and produced by SpectreVision.

Wait, what, Mack? That wouldn't be the same SpectreVision. Whose podcast network you just joined? Why? Yes. It would be log rolling already maybe, I guess. But just listen to the plot of this film and try to tell me, dear Phantom Power listener that you are not interested. Rabbit Trap is set in the 1970s and it's about get this an analog synth composer.

In the mode of a Delia Derbyshire, and she's married to a field recordist, perhaps someone in the mode of a, you know, Bernie Krause or Chris Watson or something, and the pear move into a cabin in the Welsh countryside and soon supernatural creepiness ensues. The score is by Lucrecia Dalt, and the sound design is by my guest today, Graham Reznick.

Graham Reznick is a multihyphenate creator who has worked as a screenwriter, actor, director, composer, musician, and sound designer in scores of independent films, primarily in the horror genre. He attended film school at NYU and is a frequent collaborator with his childhood friend Ti West. He was the sound designer for West's 2022 Film X starring Mia Goth and 2000 nines the House of the Devil.

You may also remember the 2012 found footage, horror film, VHS, which he also sound designed. As a writer and director, Graham Reznick created Dead Wax, a limited TV series about a rare vinyl record that kills anyone who dares play it. Graham and I definitely talked about how he approaches sound design, but this conversation went in some very interesting directions.

We talked about fairy circles, sensory deprivation tanks, brainwave entrainment, and the possible dark magic of the internet. And as we find ourselves on the doorstep of October, I would definitely call this episode Halloween appropriate. Graham Reznick is also the co-writer of the critically acclaimed video game Until Dawn.

Our Phantom Power members will get to hear Graham discuss his script writing process for video games. And Graham's amazing recommendations for what to read, what to listen to, and what to do. That's in the ad free members only version of this episode. If you want to join Phantom Power as a member and get all of our bonus episodes and other content, just go to phantompod.org or mackhagood.com.

Yes, I've been weaning myself off of Patreon and um, so our membership is now on my own website, and we'll be talking more about that later. In fact, just a couple of other things before we get started. Phantom Power is no longer just a podcast. We're starting a free Phantom Power newsletter that will drop on the second Friday of every month.

So you may have noticed that our podcast usually drops on the last Friday of the month. So now we'll have a newsletter with more interviews, book reviews, and sonic news. Just go to phantompod.org or Mack Hagood That's M-A-C-K-H-A-G-O-O-D.com to sign up.

Okay, let's get into my interview with Graham Reznick.

Graham Reznick, welcome to Phantom Power.

Graham: Hello. Thank you for having me.

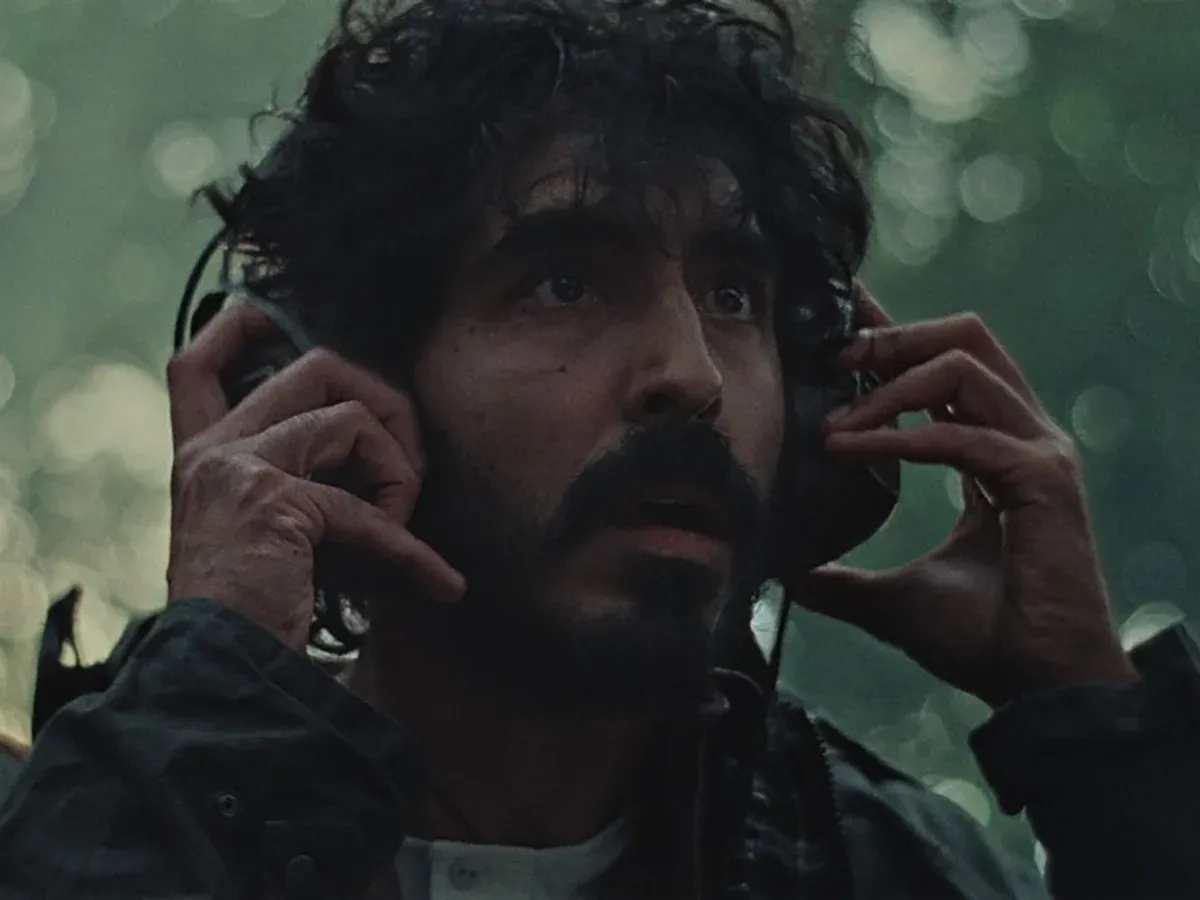

Mack: So I thought we could just start off by talking about your new film Rabbit Trap. It's this folkloric psychological horror film, written and directed by Bryn Chainey and it stars Dev Patel, Rosie Ewen, and Jade Croot. Could you maybe just sort of set the stage for us, give us a little synopsis of the film?

Graham: Yeah. So it takes place in 1976 and it's about, um, a composer, uh, Daphne Davenport. Uh, and you know, there's a inspiration from the sort of Radiophonic workshop and Delia Derbyshire and,

Mack: Yeah, I was at the, I was thinking Delia Derbyshire when I,

Graham: The alliterative names. Yeah, for sure.

Bryn talked about that. Um, yeah. Uh, so she and her husband, who's Darcy Davenport, which is Dev Patel, um, he is a field recordist.

Uh, and she's a composer and a musician. She goes to the countryside in Wales, uh, to work on her new album. And the way that she makes music is by utilizing field recordings, uh, that her husband, uh, captures, and then weaving that in sort of, uh, electronic music, music concrete. Um, then, uh, they go out to the, you know, the Welsh countryside to do this, and they're having some unspoken marital issues.

Uh, and there is some, uh, past trauma that neither of them are willing to talk about. And when Darcy goes out into the woods to record, uh, sounds for her record, he comes across a fairy circle, classic mushrooms in a circle in the woods. And he records something that he shouldn't. She incorporates that into her music and that acts as sort of an incantation and brings something else into their life.

Uh, and that else arrives in the form of, uh, a child, uh, sort of generalist, but a, a boy in the script. Um, and that child, uh, becomes a part of their, their family and begins to kind of turn everything about their reality inside out as the course of the movie, uh, unfolds all through sound.

Mack: Yeah, I mean that's, that's an excellent description of the film. Um, and definitely this whole film is completely suffused with sound. It's very much about sound. I mean, we've got this sort of Delia Derby Shire character. We've got this character who seems like Bernie Kraus, you know, like a sort of outdoor field recording type character.

Um, and then just the opening of the film really. Maybe we can talk about the opening. You know, he's outdoors, recording this huge swarm of birds, uh, and, and she's inside making electronic music. And then sort of, there's also like an opening voiceover that happens. Um, can you talk a little bit about what was being established in this opening scene and then how you approached it as a sound designer?

Graham: Um, yeah. It was daunting, um, for sure. And, and I should start by saying Bryn's script, um, which was given to me by Daniel Noah of, uh, SpectreVision and SpectreVision Radio. Uh, and who's been a close collaborator of mine over the years on different projects. Um, one of which I was the director on.

And then I've also, uh, edited a lot of podcasts for SpectreVision Radio. Um, I trust him implicitly. And I, I don't do a lot of sound design anymore. Um, I used to do a lot. Um, I still do a lot of sound design for my own projects, but I, I stopped doing it for hire as much about 10 years ago when I was doing a lot more writing and directing projects.

Um, so I'm always a little hesitant to get involved with a film that requires a lot of sound design, only because I know that it's going to completely consume me. And I want it to consume me, and I want it to be like the entire wavelength that every part of me is on, and I have to make sure that it's the right thing.

And so when Daniel brought me this script, I was like, okay, I'll check it out. I opened up the script and, uh, and I, you know, two pages in knew that, uh, this was going to consume me for the next year or two. Um, and I was happy for it to do so. Um, Bryn, uh, first time feature director, uh, but he's been a filmmaker for a long time and he is a writer.

he would describe sound in the script in ways that I haven't really seen in traditional screenplays because it's kind of frowned upon, um, which I think is, you know, an old fashioned approach to screenwriting, which is to never direct on the page. And I think that's from an old system.

Um, but what what Bryn did was when he wanted to express how the sound was, um, operating in a scene, he would sort of drop to a new line indent in a way that you don't usually indent in a screenplay. So it auto automatically kind of took you out of your, you know, comfort space of reading. Um, and he would essentially list words and ideas like wind, birds, flapping salt air, and, and just create this alchemy of, uh, ingredients that kind conjured a, a feeling.

Mack: It's like an incantation in the script.

Graham: Exactly. Yeah. Um. Yeah, when I saw that, I immediately was like, oh my God, this is amazing. And I also went, oh my God, how am I gonna do this? Um, you know, and I've said, luckily the audience is not reading the script along with the movie, so, uh, you know, they only get to see the final product and they don't get to compare it to, um, Bryn's, uh, better, uh, script.

Mack: It seems to me like there's an ambiguity in your soundtrack, like in that opening scene. It's not totally clear, which sounds are coming from the music in the studio, which sounds are being recorded in the field with the field recorder. Uh, you know, but even, you know, which sounds are diegetic, you know, like coming from within the story world itself, and which might be non diegetic or part of the musical soundtrack that only we, the audience here.

And it seemed for, to me, like that ambiguity is so appropriate to this film because it's about this uncanny space where the human world and the fairy world are overlapping and their intention with, with one another. And it, and it's disorienting.

Graham: Totally I, and that, that was another reason I was really attracted to this. One of my agendas as a creative person involved in sound because I, I feel, I feel like it's stolen valor or imposter syndrome to even say that I'm a sound designer by trade because it's something that I do often and do other things.

But there are other people who do it all the time and it's been difficult to operate in the space that I have operated in as a sound designer because I think a lot of people who. Aren't sound oriented or just part of the industry, uh, or just watching movies to them, music is violins and strings and score, uh, and sound is footsteps and birds and wind, and those are true things.

But there's also a very, very, as you said, like an uncanny space in between them. I, I've taken kind of a bastardized version of the R Murray Schafer, uh, soundscape. Uh, you know, it's not really the soundscape, but I consider anything that's in that gray area soundscape. And specifically in our Pro Tools sessions, we have, you know, dialogue, Foley sound effects, ambiance score, maybe needle drop music, uh, uh, you know, licensed music.

But I also then have a bank of tracks called soundscape, and those are things that go to the music output. They don't go to the sound effects output. Um, so anything that's tonal, um, that's. Intentionally tonal or rhythmic and intending to express an emotion. So birds in the background aren't intentionally tonal and uh, rhythmic. They can be. And that's when they verge on being soundscape for me. But, uh, and actually in Rabbit Trap they become that and some of them are on the soundscape tracks, some of the, the birds that I ran to tape and warbled and, and created a new uh, kind of thing with.

But, um, yeah, this gray area is very weird. It causes a lot of technical problems with the cue sheet and with releases afterwards. Um, but when I have the opportunity to work on a film where everyone involved is very open to this like, kind of new blend in between them, uh, you know, Lucrecia Dalt was amazing and her, her music is incredible and she really let us like take her stems, take her, her music, the editor for Brett Bachman, who edited the film, took her music and a lot of my, uh, material and combined them in unexpected ways.

And then I took that further in the final post-production process. Um,

but yeah, I mean that was like the big allure to me was we're gonna not adhere to those traditional boundaries. We're going to blend everything together, and I think that's what art and filmmaking should be.

Mack: I was recently talking to a student of mine, um, in my sound class who's very much into horror, and he was saying that he feels like there is this increasing integration between sound design and soundtrack in the horror space.

Is, is that a trend? Would you agree with that?

Graham: Oh, definitely. I mean, I, I think that's become the case. And, and I started doing sound for films 20 ish years ago, and I grew up with Ti West who did the House of the Devil, and he recently did X and MaXXXine and Pearl. Um, and we would just make movies together and, you know, in the nineties you, we had Hi8 cameras, we had mini DV cameras and we had Adobe Premier in our, you know, high school.

Um, and so we would do things in a way that is standard now, but was, you know, like a new thing then. Um, and there was really no demarcation between any of these lines to us. We were doing all the things at once. And on his first film, the Roost, uh, we worked with Jeff Grace, who is a great composer and he worked with Howard Shore on Lord of the Rings. So he, he was one of the first people to look at what I was doing alongside his work and go, oh yeah, no, this is essentially a type of music. 'cause I felt really weird.

I felt really like, uh, self-conscious about putting in layers of guitar feedback alongside his strengths. And,

Mack: Oh, yeah,

Graham: and, and he was like, no, absolutely. And that should go on the cue sheet. Those aren't sound effects. And I was like, oh yeah, you're right. It's this other thing in between. Um.

But even on, um, House of the Devil, which was 2008, uh, we had two soundtracks essentially, but only one of them was released, which was just his score. We couldn't find anyone to release. All of the guitar stuff, all of the synthesizer, drone, all of the stuff, stuff that you would like, you know, there's millions of labels and millions of bands that released stuff exactly like it.

But the people in the sort of film score releasing community at the time were like, what is this? This isn't music. Um, that's changed. Uh, and that album was released unofficially, uh, through Library of the Occult in 2022 as The Interconscious C atalog. It's all the material from House of the Devil, but it, it took 12 years or something to, to get, uh, get that seen as like actual material.

Um, and not just like effects.

Mack: did you work on the sound for Ti West's X as well?

Graham: I worked on X, uh, but not Pearl and Maxine. Pearl didn't really need, um. Design. And then Maxine was all, uh, with Formosa sound. Uh, and I had moved on to other stuff.

Mack: For folks who don't recall X was that, um, film starring Mia Goth. It, it, to me it was like, sort of like a mashup of, uh, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Psycho, and Boogie Nights. But it, but uh, you know, another period piece actually similar period to Rabbit Trap. Um, but I like I did not realize that you and Ti West grew up together.

You mean you literally grew up together.

Graham: Yeah. In Delaware, um, since kindergarten. Uh, we grew up in Delaware, um, in, uh, Greenville, Wilmington, um, went to high school, well went to preschool, uh, through high school together. So we made all of our films together. Then we went to New York. Um, Ti was at SVA and I was at NYU and he met Larry Fessenden, uh, through Kelly Reichardt.

And, uh, then yeah, we just started working with Larry and got our first features made. It went from there.

Mack: Wow. Wow. So maybe we can get back to Rabbit Trap and, and that first scene.

Graham: Oh yeah.

Mack: Because we were gonna talk a little bit about how you, you know, so you, so you see the, you read these incantations on the script, and then what happens? Like what? Like talk to me about your process.

Graham: But for that scene specifically, because we, you know, he, he was a little more, uh, he was a little less vague in terms of what the elements of that scene would be. We knew that, um, there would be electronic music being constructed in the studio, and we knew that, uh, Darcy would be recording these murmuration of starlings.

So we had a specific bird. We had specific, palette of sounds from the studio to, uh, combine. What we didn't have was actual music. We had a lot of material from Lucrecia, but I think. Only a few of the pieces that she gave the production were to picture. There was something for that scene, but I think it was, we ended up using it elsewhere, so we had to figure out something new for that scene of hers, for the music portion of it.

Um, the murmuration didn't exist because all of those flocks of birds are, uh, cg. Those aren't, you know, uh, real, uh, there was some stock footage, but it was a little challenging for me because you know, to create sound that's in sync with kind of amorphous shapes and clouds of birds, it's, it's a hard thing.

Graham: especially like with, you know, murmuration of starlings, it's like a sharp white noise basically. And, and you throw reverb, you throw effects on that. It just becomes kind of like more layers of hiss and white noise, which is hard to then shape. Um, I love all that stuff, but when you're also building like a cacophony with it, it, it, it doesn't attach to the image, um, in a way that is sustainable over many, many shots.

So there were a lot of weird little tricks that we had to do, um, around the birds to tape and, you know, would speed it up and slow them down. Um, and then layer those and then do lots of frequency sweeps, like ladder filter stuff. And, um, kind of do that along to, you know, the birds shifting positions and a lot of panning.

Um, and combining that with the oscillator. Sweeps, um, that I would just record from my synths. Um, and then that all combined with, uh, the couple stems of Lucretia's work that we used for the scene, which was there was like a low end drum pulsing thumping, and a, uh, higher pitched, uh, sort of arpeggiated synth, um,

Mack: Hmm, mm-hmm.

Graham: mixed in.

And somehow this ended up being about 200 tracks of audio.

Mack: 200 tracks. Wow. We're seeing this analog studio in a cottage in the Welsh countryside. I mean, it, I think for a lot of listeners to this show, it seems like this kind of, sort of paradise.

Um, you know, but then something goes wrong, of course. 'cause it, but, but like, it, it, it. How did you approach that? Given the fact that you're working in Pro Tools, you have all these digital things at your disposal, are you thinking in terms of, um, the time period and making sure that certain things conform, um, in the production process to what it would've sounded like in 1973?

Graham: definitely. Um, there was, uh, I believe on set and with the equipment that they're showing, they made sure that nothing was past a certain date, uh, mid, whenever it was, mid seventies, um, for us, obviously I can't mix the film on analog. It's, you know, there's one thing when you're doing multi-track recording for music, because you can get a four track, you can get a reel to reel, you can do multi-track recording on one machine for film mixing, you know, you need 20 minimum, you know, a hundred to 500 tracks standard.

And to do that in a mix room with analog gear, you know, means you have your mix room and then you have 20 to a hundred machines running tape, which is insane, uh, these days, but was standard back then. Um, and I was, was only in one of those mixed rooms once, and I was, uh, shocked, just like shocked that that's what it took just to get the most rudimentary sound mix in a film.

Um, but you know, so we're using Pro Tools to put everything together. But like most of the audio creation, most of the, um, designed audio in the film was through analog synths or through field recordings and other, you know, recorded material run through reel to reels or cassette tapes. Um, I'd like to get my hands dirty.

To me, the, the fun of joining a film like this, it was the prospect of, uh, being able to just have a couple days where I could set up my guitar pedals and set up my reel to reel and set up my little tape transport mechanisms and, uh, just go to town and record hours and hours of material.

That to me is the place where I feel the best. And, uh, and then, you know, that material then becomes like a palette, uh, and that you paint with in the film.

Mack: Wow. Interesting. So when you talk about guitar pedals, because earlier you mentioned, you know, in an earlier film, guitar feedback like, are you plugging in a guitar to the guitar pedals? What kind of pedals are you using? What's

Graham: Yeah.

Mack: What are you using to develop this palette?

Graham: Um, I, for a very long time I had one borrowed, uh, Yamaha Pacifica, which is I think a Strat knockoff, uh, that I borrowed from my friend Jeff Kraus in the nineties. Thank you Jeff. Uh, and his, uh, his, oh, it's his Crate amp, which is, uh, over there. I still have both of 'em. And um, I had a buzz box. Pedal, which was DOD pedal, which was the, it was sort of supposed to be like King Buzzo from the Melvins. Uh, but it was a, like a, you know, I think he used a rat in a blue box. Um, I don't know how deep I should get into pedal

Mack: go. Go for it. Yeah. I'm with you.

Graham: yeah, so, yeah.

Um, so the buzz box, like I got for like 70 bucks in Long Island at a, a used guitar store in the nineties. Um, ' cause it was cheap and I could get it, and it had a very specific sound and it, it, it's got like an octave, uh, thing in it and a very, very crunchy vel velcroy kind of, uh, fuzz. But, um, it really, uh, created an intense feedback when I would, uh, use the broken Crate amp along with it.

So most of what I did for years was just through those two. Oh and, uh, the original, um, Line 6 delay modeler. Um,

Mack: Mm-hmm.

Graham: so for a long time I used that. And then a couple years ago I got back into it and started using pedals as outboard gear. And just running things out through my computer, um, and into the pedals.

So I have a bunch of, um, Eventide factors, um, not the H9 because I like to knob twiddle. So, um, I got the individual factors over the years time factor, pitch factor, mod factor in the space. And I have them set up, uh, on a pedal board, uh, with a, um, Boredbrain, uh, Patchulator, which is like a, a guitar pedal patch bay, but you can also loop it through modular or whatever else.

Um, and that way I can reorder the pedals, uh, whenever I want. Uh, so if I want to have the, the pitch one go into the mod factor first, uh, and then into the delay into the space, that's a really easy rematch. Or if I want to, you know, change that around, again, very easy. Um, and actually that's how a lot of the, um.

Fairy circle sounds for the film were created. Um, I use the, uh, I think it's over here. Yeah, the Landscape HC-TT, which is the hand cranked tape transport. We can lift it without dropping it. We're on camera for some of this. Um, you know, you put a tape in because that tape down here and then it, uh, you can spin these around and it's like a reel to reel, but you have a lot more fine control over just little warbly zips and zaps.

And so, um, yeah, so a lot of the, the vocal fairy circle sound is

Mack: Yeah. Yeah.

Graham: that's my daughter singing the Barbie Life in the Dream House theme song, uh, when she was seven. And, uh, I ran that through this, uh, hand crank tape transport from Landscape, and that went through the Eventide array and yeah, that, that's how I created most of those sounds.

Mack: That was another scene that I wanted to ask you about, but in part, because it happens early and I figured it wouldn't be a spoiler to talk about it, but when Dev Patel's character accidentally, while he's field recording, walks into the ferry circle, and we hear this other world, and I, I, I don't know a ton about, you know, fairy circles in folklore, but I mean, I think there are different ways you could conceive of them.

Like maybe the fairy life is happening underground or maybe it's invisible and it's happening within the circle above ground or like, so I was just wondering like. Because you, the sounds that you create are really incredible in that moment. And, and, um, and just hearing about this hand crank tape recorder, that makes a lot of sense to me because there are sounds that are sort of like vocal sounds that make these little zip zippy sounds that do evoke for me fairies or, or just something uncanny and small and not visible.

Um, so yeah, maybe talk a little bit more about that scene.

Graham: Well, I think the, for me, sound in films is always an offshoot of writing. So, you know, I, one of the other rules that I have for doing sound design on a film, um, is that I want to get involved early. Um, but I also want to get involved in a film where there is something in the sound that progresses the narrative and expresses ideas and emotions in the narrative that aren't being expressed through other more traditional facets of storytelling, like dialogue and, you know, uh, perform character, performance, whatever else.

Um, and so, you know, for this, there is a, a narrative to the unseen audio, uh, of the film. You know, it's a, a, a character essentially, and you have this otherness, uh, you know, beyond the fairy circle in this film. Um, and we, we came up with a lot of rules and ideas for how to approach it. Um, you mentioned something about like the sound coming from the earth, and that was one of them.

So there's a, a very low kind of rumbling throat groan. Um, it's like throat singing almost. It was when I had a cold years ago. I just recorded a bunch of layers of this and then ran a tape, slowed it down, ran it to tape again, slowed it down more. So that kind of bubbles up. And it's supposed to, you know, be attached to the idea of the earth sort of churning underneath you.

And then there's also the, like, one thing Bryn and I talked about in our first meeting about the film was this idea of the, like fairy barrier. That there's this other space that the fairy circle, uh, leads to this other realm beyond. We don't get to know it, we don't get to know much about it. Um. But to me, the important thing is the membrane between those two spaces because it's something's coming through from that space.

And, you know, the, the medium is the medium specifically. The thing between is the important thing, uh, when you're talking about an encounter, uh, like this. , So when Darcy first encounters the fairy circle, he's sort of catching it on the wind. It's almost like he's tuning his radio to it and he's catching little bits of it.

Graham: And so that's where the idea of these sort of zippy voices came from. And then also, uh, there's like a detuned radio kind of sound. And at first I thought I would do that by recording some of this to tape and, you know, have, I have a little FM transmitter and you know, radio, and I've done that before in films.

But what we ended up figuring out was, um, if we took some of that vocal stuff and kind of smoothed it out and made a long texture of it. Um, and then took the sounds of mushrooms on this other fun thing I have from Landscape, the stereo field, which is really popular in noise production. Um, put mushrooms on that.

And they make these kind of, you know, these like very like kind of staticky, crackly, electrical sounds. Combining the, um, the sounds of the, uh, the, the sort of vocal presence.

With those, uh, crackly mushroom sounds and having the vocal presence only bleed through during those crackles, um, using that kind of morph technique, um, created this like really bizarre and familiar, but just slightly unfamiliar radio tuning type sound. And, and that's the key thing to me, to like, uh, express the idea of the sublime, something that's sort of familiar on a primal level, but just different enough that you're like, I don't know what this is.

And it makes your brain light up in a way that implies the unknown.

Mack: Yeah, that's fascinating. So you're actually using, um, this kind of, um, bio sonification that I, I think a lot of sound artists are, are experimenting with these days. Um,

Yeah. And I just got this actually from Instruo. This is a little, this little guy, uh, it uses two little like clips and you put 'em onto, uh, plants and stuff. I haven't played around. I just got it the other day. But yeah, it's like a, it's becoming a popular thing. Um, but yeah.

company called Plant Wave that,

Graham: Yeah. Mm-hmm.

Mack: that makes, makes one. Um, and so that's, yeah. Wow. That's really interesting to think that mushrooms are, are playing a role in the fairy circle sound itself. You know, one of the things that I was like thinking about, um, was sort of like when Dev is sort of, as you say, he's led by the sounds into the fairy circle.

He's picking up something and he, he's pointing his microphone towards it and he winds up wandering into the woods. And then I was just sort of thinking like, are these sounds. Audible in the space, or are they just, you know, an effect of the fairy world having some kind of effect on the electronics and then they're getting imprinted to the tape.

You know what I mean? Like the,

Graham: I, I believe it's, I believe it's the latter. That's the way I approached it. 'cause he takes his headphones off, he can't hear them. He puts his headphones back on. And it, it sort of relates to EVP recording and the idea of ev, which I, I worked on a film called the Innkeepers with Ti, uh, years ago. Uh, and got really into that concept.

Um.

Mack: Can you explain that concept?

Graham: Just the idea that, uh, and as I understood it, then at the time, it's, you know, I'm gonna probably not do it justice. Uh, but the idea that, uh, I think it's called electronic voice phenomena, uh, EVP, and it's the idea that electrical equipment is sensitive enough and more sensitive than human ears to hear sounds from the ether.

And I think Thomas Edison said something originally that kind of, uh, indicated this.

Mack: Thomas Edison had a a, I believe there was an interview in Scientific American with Thomas Edison, and he was convinced he was going to be able to record the voices of the dead.

Graham: yeah. He wanted like the ether, uh, yeah. The, to record that. And, and that has, you know, persisted. And I think it's fascinating. I'm in a lot of ways a skeptic, uh, but I, I love the idea of it, especially narratively. It's, it's very potent. Um, the idea that our technology can, uh, tap into these things and, my work in the fairy circle is half of it, and Lucrecia's work is the other half in the narrative.

She had given us this like absolutely beautiful metallic ringing, like harmonic disharmonic thing, and it's like a river of sound. It's really wonderful, but that is so consistent as a texture that it doesn't work for the discovery and for the membrane and for the breaking through.

Graham: and so we had, that's why we created this sort of buildup of all the little voices, all the little churning earth things, all the tuning of the radio. And then you hear this kind of, uh, metallic thing kind of bubbling through. Then when Daphne begins to process all the audio, it morphs it into that more, um, like ringing metallic sound, which is sort of like the, you know, it's like they're tapping into a current that exists beyond that membrane.

membrane.

Mack: Yeah. Yeah. Is is Lucrecia Dalt's soundtrack available for people to, to listen to.

Graham: It is, uh, I think Lakeshore and Veda Or Vada, um, is, has put that out. And then my soundtrack, uh, we are, are also working on releasing, uh, as well with all of my material.

Mack: Oh wow. That's, that's fantastic. You mentioned earlier that you, have not been taking on too many sound design jobs lately, and that's because your career spans much, much more than sound design. And, um, I got the opportunity to listen to this. Limited series that you did for shutter called Dead Wax

Graham: yeah,

Mack: and could you maybe talk a little bit about that?

You wrote and directed that, right?

Graham: yeah, so Dead Max was a show that I did for Shudder, um, in 2018. Um, and I'm a big record collector. Um, and so it's about a vinyl hunter who is searching for a record that ostensibly has, uh, the recording, uh, or has a recording that no one should ever hear. So there's some, you know, similarities between, um, the thematic ideas in Rabbit Trap, a sound that a person should never hear.

It's a, it's a classic archetype in a lot of ways. Um, it's the, the Pandora's Box, I guess, you know, archetype. Um,

Mack: Hmm.

Graham: But, uh, forbidden Media, you know, and, uh, I've, I've been a record collector for a long time and, and it, it was something I always wanted to explore, um, and had the opportunity to do that for shutter.

Uh, and so we yeah, created this narrative around, searching for sound and what sound can do to you, to your body, but through a sort of, um

low budget, low-fi, uh, very expressive horror. Uh, medium.

Mack: Yeah, I, I mean, it, it, it's, it is this sort of film noir like, you know, but the, the sort of the film, the Philip Marlow character is this woman who is sort of like. Like, I don't know, like a, like a crate digger who uses espionage techniques or something and, and, and just prides herself on being able to find these most obscure records, you know, no matter what techniques she needs to use.

Um, and it's so, it's like playful, but it's, it's also like, I mean, it sets such a good mood. Like, like, um, I'm honestly, I don't even know if there's a daytime scene in, in any of the episodes I saw.

Graham: Not a lot. Yeah.

Mack: Um, it's got a sort of like, for me, brought to mind, like David Lynch's, Mulholland Drive in that there's a lot of like medium and tight shots and it's kind of, the colors are really evocative.

Everything's kind of dark and moody, but it feels, it's almost like a surrealistic womb like experience to be in this. It's just very, I thought it was just very pleasurable and it's like,

Graham: thank you.

Mack: it's, you're doing a genre thing. It's like, it's not like serious, you know? And, and, but you take the genre seriously, I can tell.

Graham: yeah, yeah. And that, that was, you know, my, my goal of it, which was records have gotten very popular. Uh, and that was a, a wave I was able to ride to get that green lit, especially, uh, in 2016 or whenever it was that it was green lit. Um, but, you know, for a long time the general public's idea of record collectors and record collecting was like.

What the, the people Harvey Pekar and, and Robert Crumb. You know, like old white dudes just looking for old jazz records, you know, and that's a big part of it and I have no issue with that, but it is also a much bigger thing and there's much more to the allure of sound than just that.

And so I was interested in taking the sort of Kiss Me Deadly framework, um, because the movie's really modeled after Kiss Me Deadly more than anything. Um, and uh, and, and put a woman at the center of it and, uh, yeah, and find just a different way to approach the idea of rec record link. I was really inspired by, um, I don't know how to pronounce her name, Amanda Petrusich.

Oh God, I don't know. She was a great writer. Uh, I think for Pitchfork. She had a, um, an excellent book. Uh, do you know what I'm talking about? Um.

Mack: Uh, yeah.

Graham: She, she has a great book, uh, about, uh, record collecting and it was, you know, a inspiring one for, for that, uh, that show. Um,

Mack: Is it like a Petrusich.

Graham: Yes, I think so. Yeah. Yeah,

Mack: Yeah. Yeah.

Graham: A name that I've always seen written but never spoken out

Mack: Right, right. Yeah, totally.

Graham: yeah.

Mack: Well, you're, you're kind of, you know, also as I think you hinted at earlier, working in the tradition of, of a movie like Ringu with this is like a cursed recording.

Graham: Yeah,

Mack: What do you find appealing about that trope? Are there certain fears or, um, ideas that it allows you to explore?

Graham: yeah, there are, and I think with something like Dead Wax, which is using the forbidden media trope specifically to express my own insecurities, inhibitions. I think the thing that I wanna explore with it is this idea of obsession and the allure of obsession. Um, which I think is also true in rabbit trap, um, to a lesser degree than, you know, those two characters working through shame and trauma.

There's also like their obsession with their work. Daphne is so obsessed with getting her record, uh, right. That they don't see that what they're doing is kind of verging on the forbidden. Um, but yeah, I mean I, I've always liked the idea that, like to mix a bunch of metaphors like with audio you might trap something that you shouldn't have trapped and, uh, and that can be very dangerous. Um, it is sort of a, a Pandora's box thing.

Mack: for me it, I, it calls to mind, and maybe this is 'cause I'm a media scholar, but like the kinds of anxieties that people have had about media from the get-go. Right. You know, whether, whether it was, you know, Plato thinking it was gonna destroy our ability to remember anything organically.

Or, you know, that there's been, you know, a a lot of times these things get dismissively called media panics or moral panics about what media can do to us. And yet I think we do have. Certain underlying concerns. I mean, just thinking about what happened with Charlie Kirk and, and the way that that horrible, you know, spectacle was really done by the perpetrator, I think because he knew 3000 cell phones would be pointed at it.

Or to talk about its relation to like, you know, memes and video games and, and you know, which is another medium that you've worked in that maybe we can talk about. But I think in some moments we, we dismiss those kinds of concerns about media and then in the next moment we might just think, oh yeah, that's what caused it. You know, it, it was like the media did it. Um, we've got, we've had theories in, in media studies. Some of the earliest ones were like, you know, the injection model, or people would call it the silver bullet theory. It was just the idea that like, you could watch a Hitler speech and just instantly be brainwashed.

Right? And so this, you know, I don't know that these are the kinds of things that, that your show got me thinking about it.

Graham: Yeah, I mean you know, growing up in the nineties when Columbine happened, it was like, oh, those kids dressed like I did, I wore a duster. They played Doom. They listened to industrial music. Um, it made my life very difficult for a little while. Um, and, uh, not to diminish at all the horror that they unleashed, um, but you know, anybody who was sort of like that, which was a lot of kids, you know, it's suddenly the people I think are very quick to blame the things that are being consumed.

I mean, there's obviously the, the satanic panic idea and metal, but like,

Mack: Yeah,

Graham: um, it's hard to wrap your head around it now. Like it was hard then, but it's harder now. Uh, I feel like.

Especially with the idea of online brain rot and being someone who's been online since the late eighties, early nineties when I was a kid. And I remember seeing something awful begin to bubble up in the early two thousands and four chan kind of growing up and just like it to me and to relate things to Rabbit Trap in the sort of other, in some ways that always felt like a weird current of just like a third rail just running underneath everything that you just wanted to, like, you couldn't,

Mack: Yeah.

Graham: just couldn't touch it.

It would just burn you. And um, unfortunately, I think because of the pervasiveness of the way the internet has kind of like attached itself to every facet of our lives, it's impossible. It's everywhere now. Like that, that used to be a third rail you really had to dig to find, and now it's just kind of everywhere.

Beyond one little touch, you know, um, just, it has to be in the right spot, but you just push one button and then that, that third rail will you know, electricute you.

Mack: Yeah, I mean, I almost feel like there's a, been a resurgence of interest in things like, you know, magic and dark arts. And I think it, it speaks to this idea that there's something running through these networks that exceeds the sum of the parts that exceeds the technology.

You know, like whether it's just merely some kind of affect that's transmitted from one person to another somehow, or if it is indeed something almost haunted, or supernatural, like, I think there's a, there's a sense that we invent these different kinds of mediums, 'cause there are folklore about books that are possessed or haunted or, or what have you, right?

Like the, but just the sense that there are these human creations that seem to be animated by something that is greater than the human almost.

Graham: Yeah, I was thinking about that. Um, reading your book Hush, uh, this weekend, and you, you talk about the, uh, the, in the introduction you were talking about the, the Beats ad and there's something very, I,

very interesting and potentially insidious about what was being implied in that ad and to sort of combine that with the idea, um. The anechoic chamber idea of the, you know, the, the John Cage thing, which I think I heard you were talking about recently on, on the podcast, um, of, you know, you remove all sounds, you remove all external stimulus and there's still something inside you.

Um, and I, like, I, I don't know if that's necessarily a good thing, you know, and you go into anechoic chamber for an hour and it allegedly drives you crazy. Um, or, you know, for a long time you, you can't, you can't handle it. And I think that in a weird way, these little pockets of the world are like shutting themselves off from the actual web of reality that we are sharing and conjuring to keep ourselves alive.

Uh, this sort of societal complex that we're creating. Um. And they're going into these little anechoic chambers and, uh, all being driven, uh, completely insane.

Mack: Yeah. Yeah. I, I, now you've got me thinking about just, you know, these other kinds of things that I, I used to do back in the day, like for a while I was, I was actually quite interested in, well, back then we were calling it sensory deprivation or, or people call it flotation tank or, or what have you. Um, but I used to go to a place, this would be the late nineties, early two thousands, um, in Chicago called Spacetime Tanks.

Graham: Hmm.

Mack: And it was actually a pretty cool thing that I got arranged where basically I would wash all of their towels, which was like a huge job. I had to take,

Graham: I can imagine.

Mack: Take them to this like industrialized washers to wash all these towels. But then they would let me float all I wanted in, in the, you know, this dead silent, completely dark

Graham: Yeah.

Mack: saline, you know, body temperature, water that you just floated on.

And watching the things that emerge when you don't have any external stimuli, I think for me was a very revealing way to get to understand like my own senses and my own mind, um, and to think about the interplay between the inner and the outer worlds. And, and, and, um, how, again, to get back to a theme we were talking about with Rabbit Trap, that it's not always quite clear what is inner and what is outer, especially when things like tinnitus get louder when you're in a quiet space like that.

Graham: Yeah. And the, the hypnagogic state and the mind's ear, you know, like the, the, you can't necessarily expect it to be all positive. If you're not able to process it the right way, it can lead you down some pretty dark paths, which I think is the way that the fairy folk and the idea of fairy in, uh, in, in traditional weird fiction and stories is represented.

It's not good. It's not evil. It's just chaos. It's madness, you know? And, and, uh, I mean, you know, Altered States one of my favorite books and movies and, and you know, I've never done a, a flotation tank. I'm afraid to, um, I've never done LSD and I took mushrooms once too young.

Um. And it had a profound impact on me in the sense that I was made very aware that this construct that we share can go away very quickly. Just absolutely like that. And we're done and we're just floating in chaos. And, uh, I kind of clinging to that, and I think that, you know, to organically bring this back to sound, I think one of the things that I've always been really attracted to in sound design and music that uses sound design, like Aphex Twin, this idea of pushing things just to a slight uncanny place and the slight detuning and gamelans to give them a, a religious experience.

You know, which one of my favorite things like Akira soundtrack kind of led me down that path, you know? Um,

Mack: I've experienced that. I like, I've, I've, I've gone to gamelan performances in Indonesia and that effect that you're talking about because all the instruments are in pairs and then they're slightly tuned, a few cents different from one another, and it creates this, this beating, you know, they call it beating between the instruments and with the lower instruments, the larger ones, like the gongs, you can literally feel this wave just pass through your body.

Graham: yeah. It's physical. It's amazing. Yeah,

Mack: it's, it's cra it's crazy. Yeah. You could totally see how that could be deployed as a technology to help people enter, you know, a trance state. Um, and, and we got, you know, machines that do that now, binaural beats machines. Um, there's even YouTube videos that do it that'll, that you know, you can experiment with.

And those, those can be effective too, actually.

Graham: Yeah. I mean, there is a lot of power in that and the feelings are real, you know, and, and what it elicits is, is a real thing. Um, I'm, you know, in terms of, uh, flotation tanks and things like that, I'm afraid of it because I'm just afraid of what will come out of me.

Um, but, uh, you know, actually one of my obsessions is the like eighties, uh, meditation tapes and self-help tapes because they promise all these things. And I think it's mostly bullshit, but it's, um, you know's a lot of fake pseudoscience, uh, a lot of like hype, kind of like the Syntronics stuff.

I, I, uh, really loved your chapter on Environments in, uh, in, in Hush. I, uh, love those records and I had no idea. Tony Conrad was so intimately involved in the origin of that really, really interesting, but at like his selling, uh, irv Teibel. His, the way he sold that stuff then became real.

He like incanted it into reality, like all this hype. And then that's what actually it became, um. These, you know, meditation tapes took a similar, and they, they make all these claims like, oh, if you try to record this tape, there's a special tone that will then loop back onto the tape itself and destroy it.

Which is not a real tape that doesn't exist. can't do that. But they create this mindset of there being some sort of like, technology beyond what you can actually do. So, oh, if the tape can erase itself, just 'cause it knows I was copying it, well then what can it do to my mind? And it supposedly has all these tones in it and stuff that

Mack: Yeah.

Graham: creating all these subliminal, uh, uh, effects, uh, in your brain.

Um, and I, you know, I wanna believe it, but it's not true. But it, there's a fascinating narrative context to it that, uh, people do believe it and it, you know, it becomes a, a placebo in a way.

Mack: Yeah. And we're back to that idea of haunted media again, and I think what these studying these types of technologies and these, these discourses or these belief systems about the technologies, what, what they can reveal is, is, you know, the underlying values of the culture involved. You know, so, so in a traditional gamelan performance, a a lot of times, you know, there was, uh, a village was attempting to kind of balance the supernatural and natural forces.

In their environment so that they could have, you know, like a productive year when, in terms of crop yields or, or what have you. Right? And then, so there would be like someone who would take on the role of, you know, this evil witch and then somebody who was like this good dragon and, and they would battle it out and, and like, you know, the, the trancing, the binaural beats were a group process to help the community balance itself and balance its relationship to the environment around it.

If we look at the way binaural beats or the environments records or, or the Beats headphones you mentioned, you know, these are, these are all in some ways similar sonic technologies that you know, could create some kind of sense of balance too, but it's all very individualized. It's like, oh, you're gonna self optimize, you know, you're gonna listen to this tape and you're going to be able to read faster, or, you know, or you're gonna block out the haters with your headphones so you can be the athlete you want to be or, or what have you.

Um, and it's really so isolating,

Graham: Totally.

Mack: you

Graham: the insidious part to me. Yeah.

Mack: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

It's

Graham: meant to put you in these little chambers. And I think you mentioned that either in the introduction or the, or the Environments chapter where that, it used to be a very, very social thing. I think it was the Environments thing. They used to exist in a social function.

People would play them, you know, in, uh, in settings to, you know,

Mack: oh yeah. Like some of these, the, the human potential movement or like the, you know, there was like this group EST and people would play the Environment's record and like have like some kind of encounter interpersonal encounter. Yeah.

Graham: I got irrationally sad reading that part of, of that chapter, especially when you talked about how DJs would play the, some of the stuff as head music. And I was like, oh my God, we used to live in a society.

Mack: Yeah.

Graham: There used to be DJs doing that. Like

Mack: Just you're flipping through the stations and suddenly you hear a country stream or whatever. Yeah,

Graham: Oh man. I just, you know, I mean, all these things , they exist still. But, um, everything is so fragmented and so individualized, and so like, you don't have a sense of like, oh, everybody's listening to these eight channels today. And like, it is great to have a lot more options, but we also have the negative impact, which is that everybody's in their own little, tiny little, uh, hole just made for them.

Mack: yeah, yeah. Oh man. I think about that all the time because I was a huge complainer as a, as a Gen X person who grew up in the, you know, eighties and nineties, I was such a complainer about the monoculture. I felt so oppressed by Elton John and um, oh God, Phil Collins. I was like, if I hear these fucking guys one more time, I'm gonna go insane.

'cause they were just everywhere. Like everywhere you went, you just heard their voices. And it made me insane

Graham: I think it's,

Mack: sort of,

Graham: it's difficult for people now to remember to even remember or like for younger generations to understand just how pervasive, like What if God was one of us was for like three years or five years.

Mack: true. Everywhere you

Graham: fucking restaurant you went into is just, what if God, what is, oh my God.

And it just made me feel nauseous and carsick everywhere. You couldn't escape some of this stuff. Um, like if you existed in the world, you would be assaulted by things like this. Um,

Mack: And the idea that now we have, you know, a universal jukebox and I can listen to only what I wanna listen to. Like, that would've been the dream for me back then. And, and now that we live in that dream, it's, I'm realizing all the, all the upsides there was to having a shared culture as much as I loved to complain about it back then.

Graham: Yeah, I mean, I, you know, I, I, I feel the same way and I, I also have to remind myself that it's not just the fault of the iPod or, you know, the, you know, infinite jukebox. There's another side of it, which is the mega merging monoculture of corporations shrinking the available mainstream down to the tiniest, tiniest amount there's ever been.

And that doesn't need to have happened. That is, that is a, uh, a concerted effort. And, and not, you know, we, we could have all this stuff at our fingertips and a lot of new movies coming out, or a lot of new music coming out, but we don't. Like in the mainstream, we don't, it. It's, you know, you look at, uh, the eighties and the nineties and like there were so many movies coming out in theaters and so many big releases.

'cause they were getting funded and they were getting financed and they were getting released and there was room for a spectrum of different types of things. Uh, and that, that's shrunk now. There's, there's very little room for much variety in, uh, mainstream releases, which is a huge bummer.

Mack: Yeah. Yeah, that's for sure.

And I'm gonna break in here. Uh, members stick around. You're going to hear how Graham won a Guinness record for his script for the acclaimed video game Until Dawn. and you'll also hear Graham's amazing recommendations for what to read, what to listen to, and what to do. As well as a great pick of my own for an academic work on film sound design that is in the ad free members only version of this episode.

If you want to join Phantom Power as a member and get all of our bonus episodes and other content, just go to phantompod.org or That's also where you can go to sign up for our free newsletter. Phantom Power is no longer just a podcast. Starting next month, we're going to have that newsletter with.

Plenty of sonic news and reviews and interviews, all of which rhyme. Nice. Um, and so yeah, phantompod.org for that as well. I wanna thank Graham Reznick for being on the show. I love talking to him. Be sure to catch Rabbit Trap at a theater or streamer near you. It is out. And thanks to Cameron Naylor for editing today's show.

And to Blue the Fifth for our outro music. Members hang out everyone else. I'll see you next month. And by the way, lots of great stuff coming down the pike, including a round table on African music and technology, and the members of Machine Listening, talking about their recent record that is in part a tribute to the Environment Series by Irv Teibel.

Something near and dear to my heart. So lots of good stuff coming as we. You know, kind of tiptoe into fall. Alright, take care y'all. See you later.