How We Learned to Yearn for Sonic Control

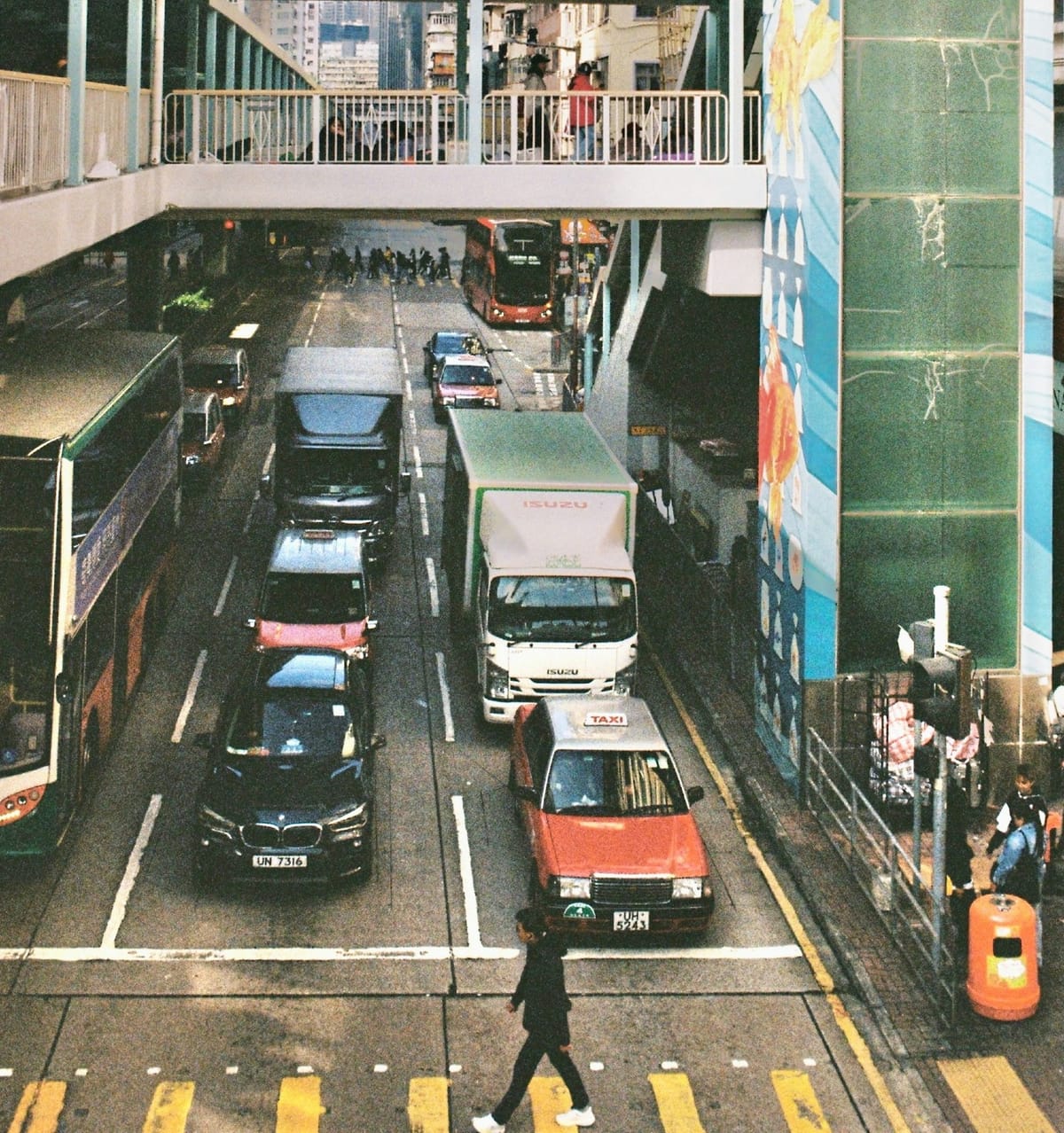

In the first installment of this series, I described the current encroachment of earbuds into seemingly every aspect of social life. Anecdotally, people seem to be wearing earbuds in settings that once would have seemed strange, rude, or simply unthinkable. But before we examine the tiny computers that live in our ears today, we need to understand how personalized listening came to feel both possible and necessary. And that's the story of how the sonic space around us lost its coherence and meaning.

Before it could make sense to put Walkman headphones over our ears in public, we had to get used to the idea of music being everywhere, at all times. The long history of radio, film and TV soundtracks, in-ceiling speakers, Muzak, telephone hold music, and so-on primed us to experience music as something less like a human performance and more like an atmospheric condition. Music became the weather of public space--something always there in the background and always beyond your control, whether you liked it or not.

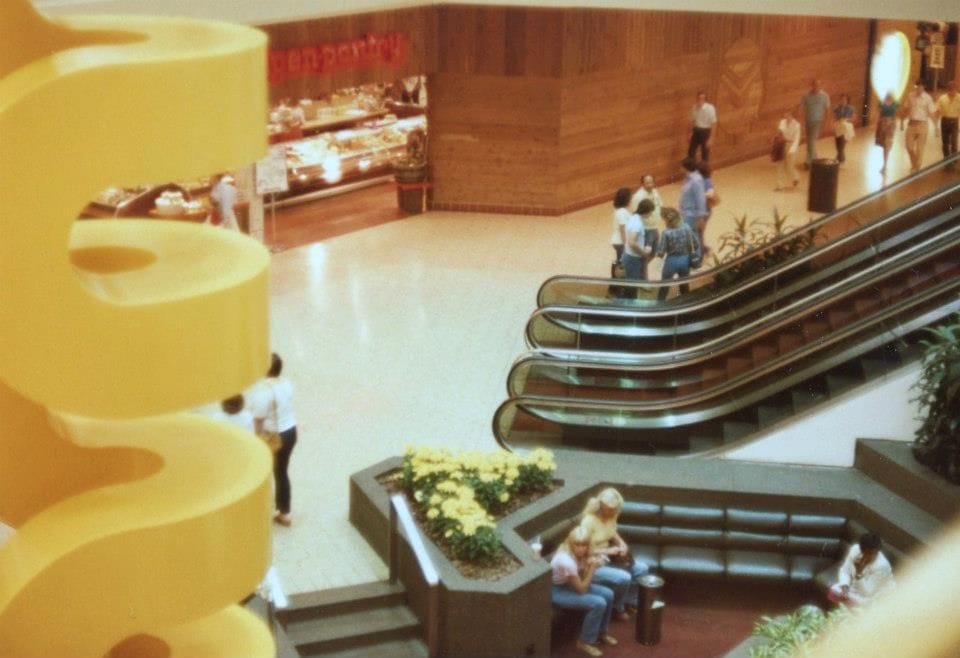

While this music was ostensibly there for your pleasure or entertainment, it was really designed to modulate your behavior--to get you to feel a certain way or work harder or eat faster or shop longer. Music had always been, in part, an instrument of power, but never had its power been so pervasively deployed. Music became an important agent in capital's colonization of shared space, when the "public" spaces we once spent our time in were increasingly converted into private ones, such as the mall.

Music became the weather of public space: something always there in the background and always beyond your control.

As this new musical weather system took hold, the Canadian founder of a new field called "acoustic ecology" began criticizing how all of these public loudspeakers were contributing to an increasingly chaotic and meaningless "soundscape." R. Murray Schafer's words from 1977 seem eerily similar to current critiques of artificial intelligence: "Today... the slop and spawn of the megalopolis invite a multiplication of sonic jabberware." But Schafer wasn't taking about the degradation of internet culture--he was upset about the corruption of the very air we moved through, filled with "slop and jabber."

Schafer has had his critics. His modernist project of perfecting our acoustic surroundings could easily be seen as elitist, among other things. But he was correct in that uncontrollable music and meaningless traffic noise had become the vibrational atmosphere in which we lived. It's hard to explain today how oppressively omnipresent Phil Collins and Elton John were in the 80s, for example. You simply had to weather the constant exposure to their drippy tunes.

And so, when we were presented with a technology that offered back a bit of sonic control, it only felt natural.

It was two developments, the musical colonization of public space and mobile radio's privatization of listening, that primed us for the Sony Walkman.

In his textbook Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman, Paul DuGay describes an interplay between the twentieth century soundscape and "the soundscape of the mind... a sort of 'second world,' adjacent to but separate from the everyday one." We had always had an inner sonic world--we remembered songs, imagined voices--but now technology could transport us there in a more vivid and effective way.

The first technologies to help us craft and cultivate our interior soundscapes on the go were not the Walkman, but the portable transistor radio and the car radio. DuGay writes that they took "the pleasures of private listening into the very heart of the public world and the qualities of public performance into the privacy of the inner ear."

It was these two developments, the musical colonization of public space and mobile radio's privatization of listening, that primed people to desire the Sony Walkman. Next time, we'll take a look at the public reaction when the Walkman was introduced. The debate it spawned couldn't be more relevant to today, when we worry and argue over the ways our devices separate us and divide our attention.